Day 0

So after recieving no replies to an earlier post asking about how much I was allowed to prepare, I decided that it was OK to go ahead before the starting gun so long as my work wasn't directly related to the final product.

The first step would be to decide what tools I would use to bring this so-called Fantasy RPG Card Battle Game to life. At first I was considering going with LÖVE, but ever since LOWREZJAM 2018, I couldn't help but find it lacking when it comes to longer-form jams like this. Unless I was willing to sit through hours of boilerplate code and class coupling, I figured that it wasn't going to cut it this time. Enter Godot, an engine that I've been trumpeting from the rooftops ever since the release of it's third major version, but never actually finished anything with. like LÖVE, it's free and open source, but it has an edge for an RPG like this in that it features its own shading language and user interface system, which is integral to a turn-based RPG like this.

Now that I'd chosen an engine and a language (I'll be using GDScript for this one since it's the one I'm most comfortable with) it was time to take a critical look at how I was going to stick within the rules. Rule 1 is a bit of a bust, since as far as I know my direct inspiration doesn't run on the original Game Boy models, but rules 2 and 3 I knew I could clear before the jam even started!

Setting up the resolution was fairly simple. Once I'd muddled my way through a few keyword searches I could staple down the default resolution to the required 166x144, and configure the game's window to be resizable by default in such a way that the viewport always maintained the correct aspect ratio and filled the center of the screen, with 2D, nearest-neighbor scaling.

Getting the game down to four colours was a little more tricky. I could just make all of my assets in four colours and call it a day, but what if I don't like the colours later on? I'd have to go over every sprite, background and nine-slice just to sharpen up the contrast! Even worse is when someone else doesn't like my colours. With so many people playing and rating games, how am I going to ensure that I keep everyone happy? What if I could just make my assets in linear greyscale and just tell the game which colours to use instead? This sounds like a job for...

...Shaders!

Shaders are computer programs specifically designed to tell your graphics card what to do when it comes to putting things on the screen. Your typical shader has two main components; the vertex shader and the fragment shader. The vertex shader runs once for each vertex in a mesh (which could be each corner of a sprite or other texture) whilst a fragment shader alters each pixel currently visible to the projection. By changing the properties of each, you can create a whole host of different effects, like heat haze, motion blur and cartoon-like cel shading.

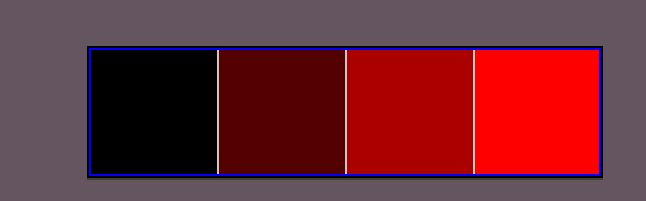

Unlike most things you do on the CPU, shaders require a bit of forward planning. In an idea I totally didn't steal from the web series Makin' Stuff Look Good, we'd use a palette sampler texture like this one:

and use it as a horizontal lookup table. For each pixel on the screen, we figure out how red it is as a normalised value between 0 and 1, and replace it with the colour found at that location on the palette. Brighter grayscale colours would have higher quantities of red light in them, and would therefore be replaced with brighter colours, so long as the palette was sorted from left to right as above. If we ever decide that the palette is inappropriate, we just load a different texture.

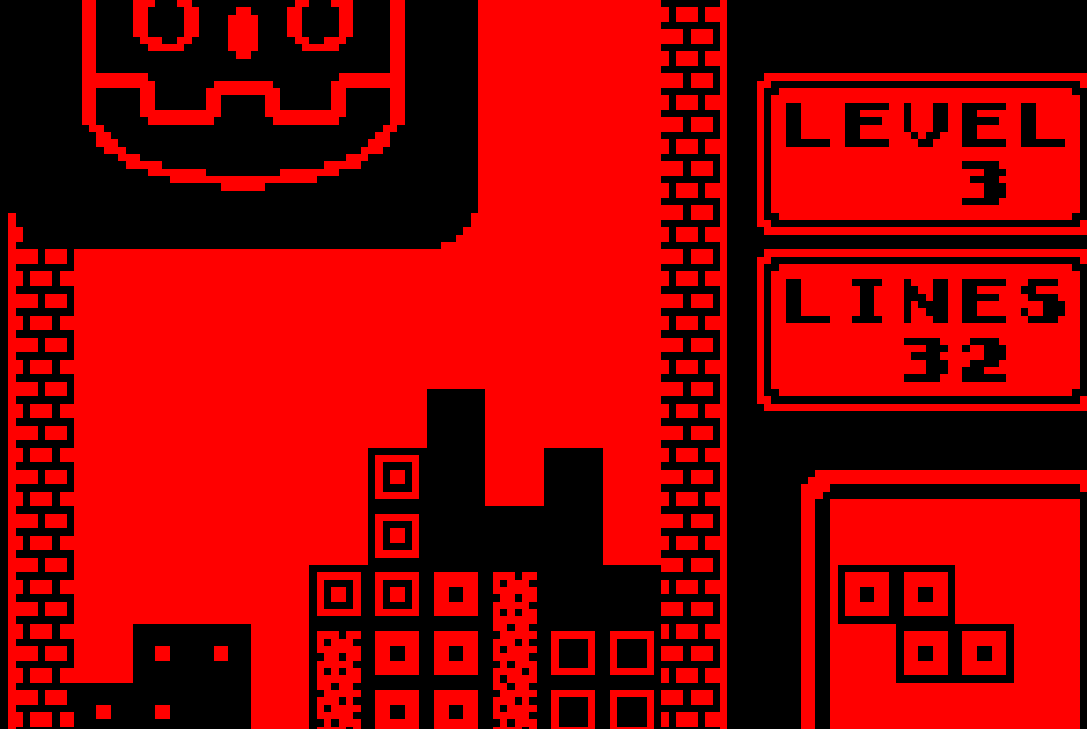

After my brain adjusted to the fact that screen-space effects have to be applied to an object in the world with the projection as a parameter instead of a script telling a camera to draw a projection using a shader, I grabbed Aseprites official Game Boy palette and hit Play:

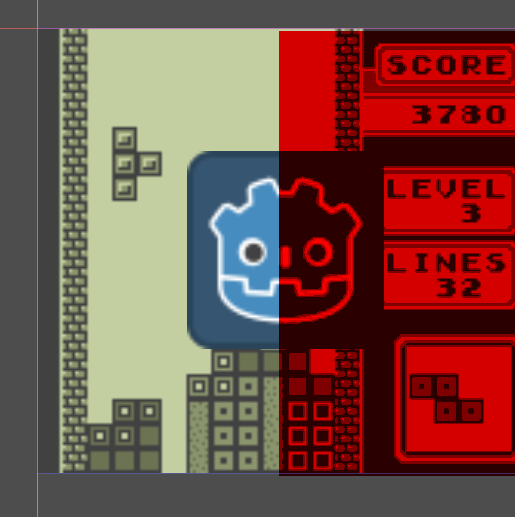

At first, this looked great! Not only had the shader converted the greyscale Tetris screenshot, but it had also converted the default Godot icon, which had it's own set of colours. But something about it felt off. Looking a little closer and opening it up in Aseprite revealed why:

All of the colours were ever so subtly different. It's most obvious at the edges of things that are supposed to be anti-aliased. It turns out that by default, Godot attempts to make your textures look smoother through a process called Billinear Filtering, in which the colours of each texture fragment are averaged out with that of the adjacent colour in the texture, blurring them together. As of writing it, I haven't found a way to reliably turn this off, but I have found a way to ensure that only a fixed number of colours are displayed. This meant that the shader was finding the correct texel, but it was a floating point value on a much larger texture, meaning that each fragment returned it's own value.

At first I tried converting the entire image to greyscale before applying the colour swap, but that didn't do anything. After someone suggested that I might be able to use posterisation to limit the amount of colours on-screen, I tried rounding the x value in the shader to see what would happen:

Perfect one-bit colour. This would be fine if I only wanted to use two colours in my game, but I knew that I and anyone else using this shader would need the full four. I'm terrible at maths, but that same person suggested that I could use the following formula to round in even increments of the whole:

x = round(x * a) / a

where x is the horizontal UV location of the desired colour, and a is the total number of colours. it then took a bit of tweaking for the shader to be sensitive to the width of the palette in pixels, but thanks to Godot's handy textureSize() function, I now had a robust effect I could be proud of:

It's still not perfect, mind you. Creating the texture images required by the shader is slow and reading them is even slower, but this is more than capable for my needs. I think I'm ready for this.

If you want the shader, it's free on Github: https://github.com/ItsSeaJay/godotboy