Before my last blog post, I had some ideas floating around on how to solve my problem with being limited by morph targets. After studying how Impossible Creatures approached its "modular" creatures, I was pretty sure I was on the right track. Exploring that direction gave me pretty good results, but also paved way to a way bigger problem, that I still haven't solved. Anyway, let's start from the beginning.

When I first started the Invocation Prototype, I wanted to have different character parts being randomized for a lot of variation. That is super simple and standard for characters that actually have good geometry to hide the seams (e.g.: clothes), but my creatures needed to be bare naked. I started by trying to merge vertices together automatically, but that had poor results, and I always ended up breaking something (either the hard edges that I wanted, or the UVs).

Now, here's what happened to me, and I guess this is a very common thing amongst technical folks exploring solutions. Going back to square one usually involves answering the question "what exactly do I want to achieve?"- and sometimes you're so deep into one idea that your answer gets biased by that.

On my first approach, I answered that with "I want to weld vertices that are close enough to each other together".

Let's go back to the very basics. then. All meshes are comprised of triangles, and those triangles are defined by vertices. Triangles are one sided, so you need a normal to define which direction a triangle is facing.

However, in a game engine like Unity, the normals aren't stored per triangle, but per vertex. This allows you to interpolate between the triangle's vertex normals to create the effect of smooth shading. If you have a mesh that is to be rendered smoothly, but you want hard edges, you need to add extra vertices to that edge, so that you can define neighboring triangles that visually share an edge, but seemingly face different directions because the way the gradients end up being calculated. This is obviously terrible to understand in text, so just watch the video below:

So taking a step back: what exactly did I want to achieve?

"I want to combine meshes with no visual seams."

That doesn't really mean that I want to combine vertices, or reduce their amount, which was my original attempt. That only means that I have to make sure that the triangles line up (i.e. the "edge" vertices are in the exact same position), and also that the normals make the shading smooth between these neighboring triangles. But how to do that automatically?

Here's the thing: computers are really good making very specific, repetitive tasks, which we suck at. However, we're really good at detecting abstract patterns, which is something that is really hard for them to do because we really suck in describing in a logical and explicit manner how exactly we detect those patterns - basically because we just don't know exactly how that works (and my bet is that we'll probably find out the definitive answer for that while trying to teach computers to do the same).

After studying the workflow used for Impossible Creatures, I realized that maybe it was better cost/benefit to focus my attempt into creating a good workflow for helping the computer in the part that it sucks with. This is especially true because whatever algorithm I'd end up using would require to do things runtime, so I'd have to optimize a lot even to prove the concept. So taking the question one step forward:

"I want to make an open edge from a 'guest' object 'lock' onto an open edge from a 'host' object in a way that there are no visible seams. Also, this has to happen in run time."

So here was the idea: I'd tag the vertices in both edges, and the vertices from one object would be transported to the equivalent position in the other one, then the normals would be copied from the host object to the one that was latching into it.

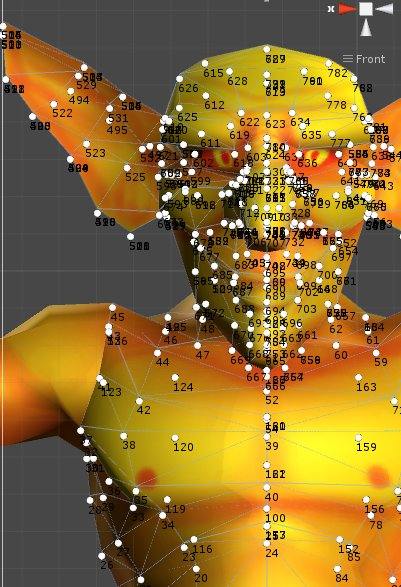

I started out by experimenting with adding handles to every vertex in the object so I could identify and manipulate them, but it was quickly clear that approach wouldn't scale well.

I don't really need to tag vertices, I need to tag what I think vertices are. So let me help you help me, Mr. Computer: here's a Vertex Tag. A Vertex Tag is a sphere that fetches all vertices that might exist within its radius. With that, I can, outside of runtime, cache all the vertex indices that I visually classify as "a vertex in the edge", even if those are actually multiple vertices - i.e. a translation between what I'm talking about when I think of a vertex and what Unity thinks a vertex is.

Snippet

public void GetVertices() { VertexIndexes = new List<int>(); Vector3[] vertices = GetTargetMesh().vertices; Transform trans = GetTargetTransform(); for (int i = 0; i < vertices.Length; i++) { Vector3 worldPos = trans.TransformPoint(vertices[i]); if (Vector3.Distance(worldPos, transform.position) < Radius) { VertexIndexes.Add(i); } } }GetTargetMesh() and GetTargetTransform() are just handler methods because this might work with either MeshFilters or SkinnedMeshRenderers. As you can see, this is not optimized at all, but that's not an issue because we're not supposed to do that in runtime.

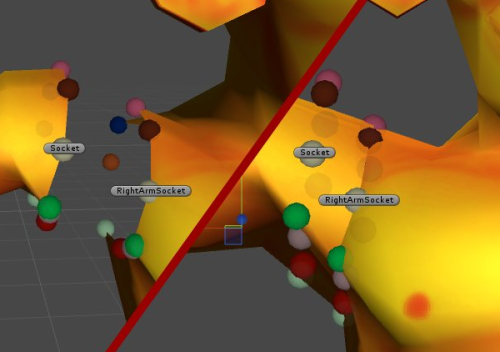

Now we need something to control a group of tags: a Socket. A Socket is comprised of several vertex tags, and it defines where things should "connect" in space. That way, we use the sockets to position the objects themselves (in a way that they properly align), and then can control all the tags to be "joined" to the proper vertices. Right now it's working on top of the tagged vertices only (so the further apart the objects are, the more deformation it causes), but it would even be possible to think about something like using verlet integration to smoothly "drag" the neighboring vertices along - which for now really seems like overkill.

One big advantage of this Socket system is that it can be improved to try and adjust itself to different amount of vertex tags in the base mesh and the attached mesh: if there are more vertex tags on the host object, you might force the host object itself to change, or you can make all the extra vertex tags of the guest object to go to the same tag in the host object. Obviously, the best thing is trying to keep the amount either equal in both sides, or very close to that. Also because, I mean, poor guy.

To make things decoupled, there's this helper class that actually has the "joining" logic: re-positioning the parts, triggering the socket to connect itself to a "host" socket. One thing to keep in mind is that if you mirror an object by setting its scale to -1 in one of the directions, you'll have to adjust your normals too:

Snippet

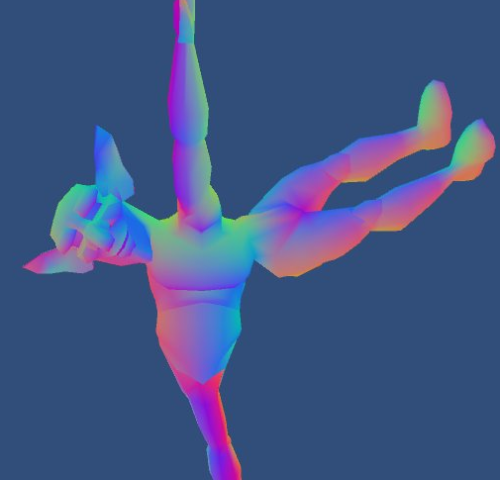

public void MirrorNormals() { Mesh mesh = Mesh.Instantiate(GetTargetMesh()); mesh.name = GetTargetMesh().name; Vector3[] normals = mesh.normals; for (int i = 0; i < normals.Length; i++) { normals[i].x *= -1; } mesh.normals = normals; SetTargetMesh(mesh); }There is some debug code in which I can see the direction normals are pointing, and the position of vertices, but my biggest friend has been a shader that paints the model based on the vertex normals (I'm using one from the wiki).

So there, now I can tag vertices, save that information to a prefab and simply get them to connect at runtime, with little overhead because everything is pre-tagged. Although the workflow isn't perfect, some small things can improve it a lot, like snapping tags to vertex positions, improving the way that sockets join vertex tags etc.

I'm so glad the biggest problem was solved, now I can simply start animating the characters.

That maybe have different bone structures for each limb.

Which have to be merged in runtime.

Hm.

I guess it's time to start asking myself the "what exactly do I want to achieve?" question again - although with a problem like animation, it's more like "what am I even doing?".