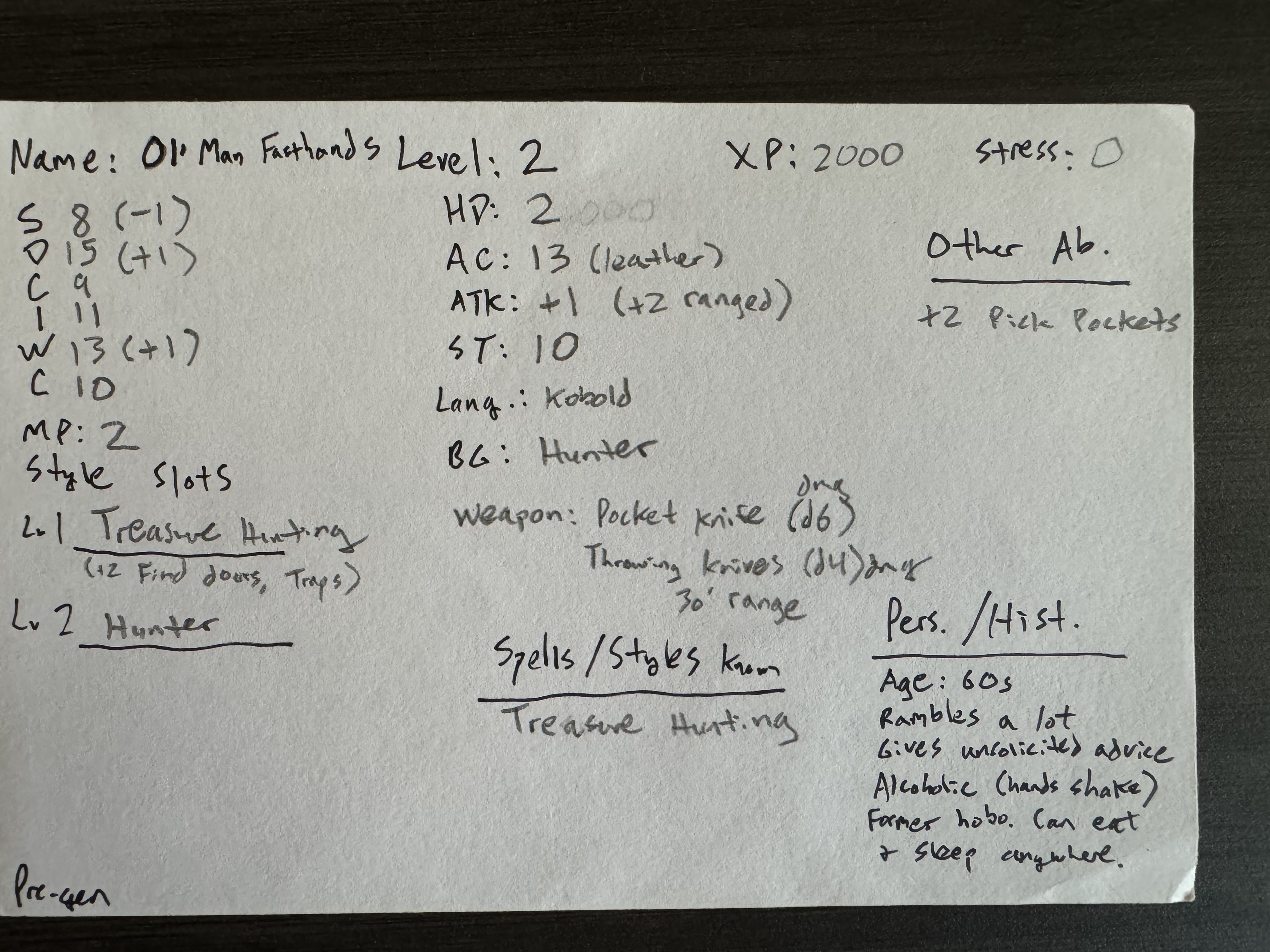

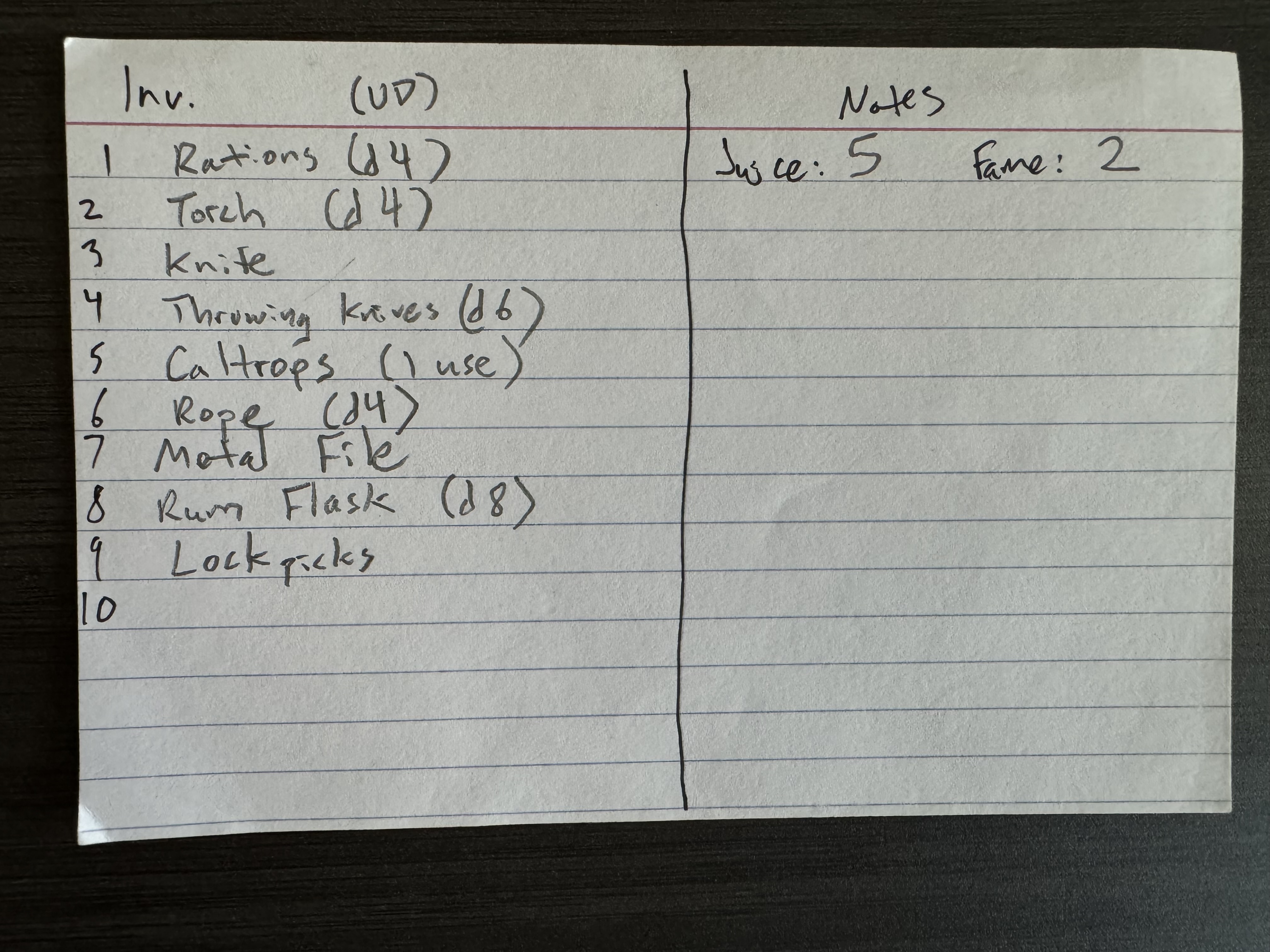

I don’t know how helpful this is but this is what I’ve been giving players for my current game. These note cards reference some stuff from outside of OSS and feature some rules changes (like there being only one save) but overall should probably work.