It's a common perception in online RPG discussions to view discussions of RPG Theory as either inherently toxic or so likely to become toxic as makes no difference. Having participated in some RPG Theory discussions at various times and various places I can attest that there is evidence for this view, it is not unheard of to see acrimony, bad-faith arguments, etc., on this topic. I'd like to discuss what, if anything, causes this, and also what might be done to try to improve discussions. I'm going to list some ideas I've had on the topic, but they are certainly not definitive or exhaustive.

Is it really that bad? One thing that's worth considering is that it's not unheard of for people's perception of a problem to be at odds with reality. For example, it's a well-documented phenomenon that people can believe that crime is rising in their city when it is fact falling. Things like sensationalized news stories can give people a sense that something is a big problem even if, statistically, it's not. Are RPG Theory discussions more toxic or acrimonious than other types of discussions? Do we have any data, or are people mostly working from gut feeling?

Status Quo Maintenance: The perception that RPG Theory talk is toxic tends to discourage new people from participating in the conversation, while those with high enough status to avoid criticism can still talk about it if they want. This can reinforce existing status hierarchies, for good or ill.

Moralized Language: We know from politics that incendiary or moralized language can lead to increased support from supporters and increased anger from enemies, so it's not surprising that politicians and commentators lean on it much more than nuanced, thoughtful analysis. A similar pattern can happen in theory talk.

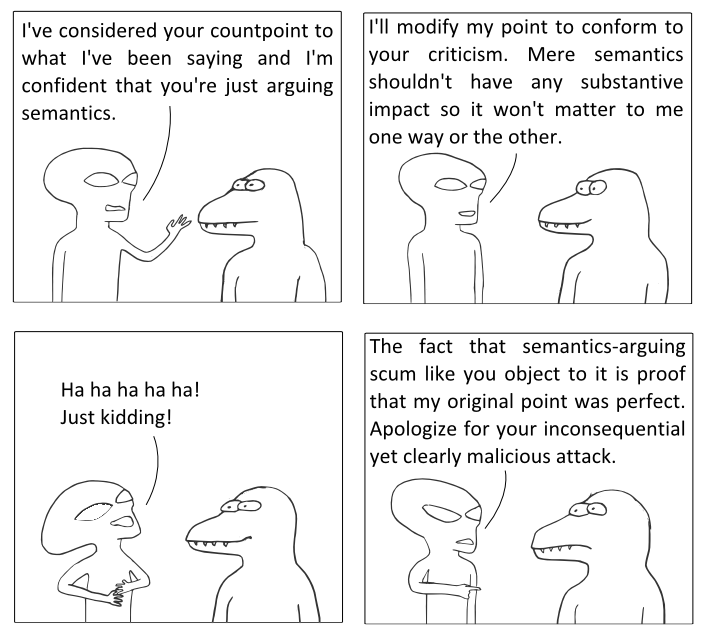

Trying to win arguments rhetorically rather than analytically: A lot of notorious RPG Theory topics seem to be associated with particular turns-of-phrase or wise-sounding aphorisms. These sort of things might be more prone to causing breakdowns in discussion than analyzing things on the merits.

Taxonomy may be a questionable approach: A common theme in some RPG Theory approaches is to "taxonomize" various things, such as GNS Theory's attempt to classify a series of "Creative Agendas" or Robin Laws' player-types. While putting things into categories or affixing labels isn't always intrinsically harmful, it runs so closely to insulting people or establishing hierarchies of value that it can often slip into that, either intentionally or unintentionally. Additionally, there's a risk that affixing labels can cause an illusion of explanation: if I say "the reason you have an intense fear of spiders is because you have arachnophobia" it looks similar in form to an explanation, but actually doesn't do any of the work of one -- you've just put a name on the phenomenon. Rather than trying to taxonomize things into groups, I suspect an "anatomy first" approach -- where the effort is to understand how particular games (or games in general) work -- probably leads to fewer hard feelings.

Bad Theories: It's not clear that there's much value in some of the past theorizing that occurred. There's definitely some that I personally think led to wrongheaded dead ends. As such it may seem like a low ROI activity to many, and may seem worth frowning on regardless of whether it is actually toxic or acrimonious.

Conflicting interests: Being seen as an expert on how games work is probably beneficial for a game creator, so there are a lot of incentives besides "is this true?" that can be in play when people pontificate about Theory. It's hard to be aware of how your own biases can distort your perception.

Psychology: People who post about RPG Theory are just as susceptible to things like Confirmation Bias as anyone else.

Those are some of my initial thoughts.